At the start of SPEED (Jan de Bont 1994) there is, for a second or so, darkness and the distant sounds of rolling metal. Then as the camera begins a very long descent of an unfeasibly deep lift shaft, the music starts.

The overwhelming visual and aural impressions are of highly polished metal, metal running on metal, the grind of the lift mechanism and a distinct sense of unease. Where's the bus? We know the film is about a bus which can't go below a certain speed or else it will explode. Why aren't we seeing a James Cameron-style slow ascent over a shining bus chassis as it waits in the depot, or the close-up preparation of the bomb by anonymous hands? Easy - because by the time we know about the bomb it is already on the bus and the bus is moving, also because we first need to meet the bomber in normal, unthreatening surroundings. Above all because the director has decided to place all the credits at the top of the film which, once the tale kicks in, will be moving too fast to allow them the time to register. So we get a lift shaft. Descending. To the mythical pit of hell, or at least to some basement place where Dennis Hopper's dark deeds can happen. And while we are in that long, long, long descent, the composer will proceed to tell us everything about the film we are about to see… even how it ends.

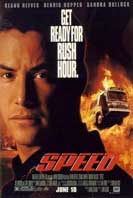

Opening titles are hard, but they are also the most rewarding part of a film to score. They are the final destination for a journey which has begun with the first publicity still or poster some year or so previously. We the public have been promised a particular cinema event, an adventure, or a love story or a comedy or a horror. We have expectations - if the publicity carries the strapline 'Scarier than Carrie' then we hope that it is, but we particularly know what the producers intended to rip off when they embarked on the project. They also know we know. We are trying to second guess them ('Carrie was the scariest film ever... no way can this be scarier...') while they try to second guess us by giving us what we want but not necessarily in the way we expect it. Now rewind for a moment to a conversation in a producer's office some time in 1992.

'A bus, right... which can't slow down...' - how lame does that sound? A bus is not a sexy hunk of metal like a railway train or a transatlantic liner. A bus is what we go to work on. It is shabby, utilitarian, its... a bus, for crying out loud. 'Aah... but we can get Keanu Reeves...'. Aaah. OK, show me a script...

And, amazingly, Graham Yost and Jan de Bont come up with a cracking, fast-moving thriller script which whips us along with nods to The Wages of Fear, Die Hard and The Taking of Pelham 123 and delivers us breathless at the end of the story with a silly grin on our astonished faces. OK, we still have a problem with the fact that most of the action takes place on a bus, but even that's alright. The film features a bus, but it's not about a bus. It's about somebody mad enough to do anything to harm innocent people and two characters, one ordinary, one extraordinary, who are brave and resourceful enough to stop him. And what is the common link in all this mayhem? From the moment in the first two minutes when Hopper plunges a screwdriver into the guard's ear until the final screech of the subway train as it comes to rest across the street, we have seen the potential and actual effects of metal hitting flesh... at Speed.

Now we see what's going on with that lift shaft. Metal predominates on screen and soundtrack. The rolling metal has an unpleasant grinding sound... and now Mark Mancina's music is growing out of that metallic miasma with a high-pitched electronic string sound falling a half-tone. We have been here before. That is a musical device we have heard through the work of Bernard Hermann, Alex North, Frank de Vol, John Williams - it is the sound of something out of kilter with the rest of the world, something just out of sight of the camera. Something threatening. As the lift shaft girders go by a slight whoosh of wind or proximity, ethereal, not part of the metallic world, cuts across the music and the other sound. We are being carried into this threatening world and those girders are just a little too close for comfort...

Then, in the practical world of Hollywood contracting, the stars names have gone and the title is due - from a growing orchestral chord with horns ululating like sirens the title crashes like an arrow across the screen, complete with the sound of jet propulsion. Speed. This title sequence could have grown slowly out of darkness, the title itself coolly arriving unannounced as in a Woody Allen film, or crashing in out of nowhere like Blade Runner, but the public have had their expectations unfulfilled for long enough. Here's the film we promised you, folks... off we go. Like a javelin the title is aimed straight at our heads and in comes the music we've expected all along. In musical terms the crashing title has provided a bridge from the slow, uneasy langour of the opening titles to a change of pace and style. The percussion is now foremost, making the most of Dolby surround (none of this soundtrack complexity would have been possible before Dolby) and the horns repeat the strings half-tone fall only now it is the doppler effect of a horn passing at speed. Consider how this tone-poem to an out-of-control bus is so much more thrilling than the visuals could ever be. The music is promising us excitement (our primary reason for buying a seat to this particular flick) but more excitement than we could even imagine, and we regular cinema-goers can imagine a lot. We've seen an awful lot of crashing, exploding vehicles. OK, we haven't seen many out-of-control buses but we are beginning to imagine how much of a gas this film is going to be. The music is no longer scaring us, it's taking us on the best of white-knuckle rides, the kind of scares we love and queue for more. And still that lift descends, although, to be frank, we're not really in the world of the lift shaft any more. From the piledriving rhythm comes the first hint of a tune, a tune which sounds slightly vulnerable amongst all this testosterone. It barely gets a chance to establish itself before the accompanying music resolves into a minor chord and leaves the percussion isolated, preparing a slower, more dignified tempo. This is another bridge, but into what?

Composer Mark Mancina has a problem which is also a wonderful opportunity. He has a credit sequence to fill during which time we have almost nothing to watch except some names which have already brought us to the cinema and other names about which we care nothing at all. This sequence lasts 2 minutes 50 seconds, a vast amount of time for a film composer to fill but also an unusual amount of time to be allowed to fill - enough time for an overture. For this piece of music to work the public must still be kept guessing. Hence the musical changes, the sense of marking time with the drums as we enter into a third world after the scares and the white-knuckle ride. Now we are in a world of certainties.

Up until now, the music has led us through a world of senses and impressions. We have felt our flesh creep, we have felt the wind in our faces as we are carried at speed, but now we are feeling something internal rather than external. The music is appealing to our emotions. It has two tools with which to do this - a noble-sounding French horn�and a tune. As an audience we respond to tunes directly because the music in a tune has a path we can follow. If that path is fairly predictable, resolves in ways we recognise and possibly arrives back at its starting place we can assimilate that tune and own it ourselves. It has a sense of security about it, even if it is in a minor key and tells of sadness and loss - at least it is a sense we can all share. If, however the tune doesn't resolve but seems intent on following an unpredictable line to a place which we find strange and unable to own, the music produces a physical sense of discomfort. If it is music alone, we might switch it off - if it is allied with pictures we would fear the worst. No problems with this tune though because, once again, we have been here before. The tune is short, only four lines to be repeated, and is drenched in an emotion which takes a while to register because we are unused to hearing it so boldly spoken, except in pastiche... heroism. The French horn, since the seventeenth century, has carried the noble weight of Royal themes, themes of ambition and achievement, themes which seem to speak of the highest causes to which man can aspire. Take our Speed horn tune and slap it over a film about Shackleton or Abraham Lincoln and it would sound perfectly in place. It soars where the percussion can only bluster. Not that we are, in our minds, necessarily saying 'Hmm, that's a nice horn tune...' - but deep inside us something very primal is responding to this horn call and linking it in our minds to something else we have been promised by the film-makers... Keanu Reeves.

We want heroes in the cinema, people who can achieve what we can only dream about (Keanu Reeves) but we would like to think we could cope if thrown into the same situation (Sandra Bullock). The music is telling us that humanity achieves heroism even in this world of flying metal and screeching steel. The flesh can fight back. First the tune happens over a held bass note, as if emerging into the light still unsure of itself - then it reappears with all the elements of the orchestra supporting it in glorious counterpoint, then from the tune emerges a beautiful set of variations which maintain a sense of humanity as the percussion re-enters and the higher instruments fly off into airy descants. Now there is no hint of metallic dread, only the mathematical dancing of a well-scored symphony in which the music is confident, complex and mercurial, like John Williams scores for the chases in Close Encounters or Superman. Music has won the day. Heroism and humanity triumph in this piece of music. Ultimately, the forces of right will triumph in the film. It will be scary, exciting and involving, and it will have a happy ending. Even when the music has to metaphorically calm itself down as the lift reaches the basement and the strings return with warning harmonies we remain in the secure world the score has established. The Caution sign we see in the first shot is the same sign we encounter before a Disneyland ride. We've paid to be thrilled, let the thrills commence. But this film is not Se7en, we are assured of no long-term disturbance to our equanimity. It's just a bit of fun... after all it's about a runaway bus for Pete's sake.

Now watch the opening titles of Speed with the volume down and see how much of that you get from visuals alone.